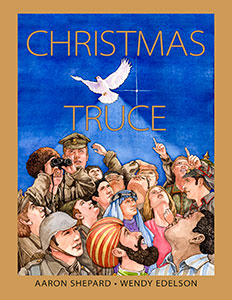

Here is the author note from my picture book.—Aaron

The Christmas Truce of 1914 is one of the most extraordinary incidents not only of World War I but of all military history. Providing inspiration for songs, books, plays, and movies, it has endured as an archetypal image of peace.

Starting in some places on Christmas Eve and in others on Christmas Day, the truce covered as much as two‑thirds of the British–German front, with French and Belgians involved as well. Thousands of soldiers took part. In most places, it lasted at least through Boxing Day (December 26), and in some, through mid‑January. Perhaps most remarkably, it grew out of no single initiative but sprang up in each place spontaneously and independently.

Unofficial and spotty as the truce was, there have been those convinced it never happened—that the whole thing was made up. Others have believed it happened but that the news was suppressed. Neither is true. Though little was publicly reported in Germany, the truce made headlines for weeks in British newspapers, with published letters and photos from soldiers at the front. In a single issue, the latest inflammatory rumor of German atrocities might share space with a photo of British and German soldiers crowded together, their caps and helmets exchanged, smiling for the camera.

Historians, on the other hand, have not shown much interest in an unofficial outbreak of peace. The first comprehensive look at the event came only with the 1981 BBC documentary Peace in No Man’s Land, by Malcolm Brown and Shirley Seaton, and their 1984 companion book, Christmas Truce (Secker & Warburg, London). The book featured a large number of firsthand accounts from letters and diaries. Nearly everything described in my fictional letter is drawn from these accounts—though I have heightened the drama somewhat by selecting, arranging, and compressing.

In my letter, I’ve tried to counteract two popular misconceptions of the truce. One is that only common soldiers took part in it, while officers opposed it. (Actually, few officers opposed it, and many took part.) The other is that neither side wished to return to fighting. (Most soldiers, especially British, French, and Belgian, remained determined to fight and win.)

Sadly, I also had to omit the Christmas Day games of football—or soccer, as called in the United States—that are often falsely associated with the truce. The truth is that the terrain of No Man’s Land ruled out formal games—though certainly some soldiers kicked around balls and makeshift substitutes.

Another false idea about the truce was held even by most soldiers who were there: that it was unique in history. Though the Christmas Truce is the foremost incident of its kind, informal truces were a long-standing military tradition. During the American Civil War, for instance, Rebels and Yankees traded tobacco, coffee, and newspapers, fished peaceably on opposite sides of a stream, and even gathered blackberries together. Some degree of fellow feeling had always been common among soldiers sent to battle.

Of course, all that has changed in modern times. Today, combatants kill at great distances, often with the push of a button and a sighting on a computer screen. Even where soldiers come face to face, their languages and cultures are often so divergent as to make friendly communication unlikely.

No, we should not expect to see another Christmas Truce. Yet still what happened on that Christmas of 1914 may inspire the peacemakers of today—for, now as always, the best time to make peace is long before the armies go to war.